Censorship in the Empire of Japan

|

Read other articles:

2005 British television programme For the 1997 game show hosted by Greg Proops, see Space Cadets (game show). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Space Cadets TV series – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Space Cadet...

Кыска-кюй Направление башкирская и татарская народная музыка Истоки народная музыка Время и место возникновения XVIII век Годы расцвета XX век Родственные Узун-кюй Кыска-кюй (башк. ҡыҫҡа көй, тат. кыска көй от ҡыҫҡа — короткий, көй — напев, мелодия) — жанр башкирског�...

Questa voce sull'argomento hockeisti su ghiaccio canadesi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Reginald Smith Nazionalità Canada Peso 70 kg Hockey su ghiaccio Palmarès Competizione Ori Argenti Bronzi Giochi olimpici 1 0 0 Per maggiori dettagli vedi qui Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Reginald Joseph Smith, detto Hooley (Toronto, 7 gennaio 1903 – Montréal, 24 agost...

American judge Xenophon HicksSenior Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth CircuitIn officeMarch 1, 1952 – November 2, 1952Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth CircuitIn office1948–1952Preceded byOffice establishedSucceeded byCharles Casper SimonsJudge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth CircuitIn officeMay 23, 1928 – March 1, 1952Appointed byCalvin CoolidgePreceded bySeat established by 45 Stat. 492Succeede...

Le tenebrose avventure di Billy e Mandyserie TV d'animazione Logo della serie Titolo orig.The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy Lingua orig.inglese PaeseStati Uniti AutoreMaxwell Atoms ProduttoreVincent Davis MusicheGregory Hinde, Drew Neumann, Guy Moon StudioCartoon Network Studios, Hanna-Barbera Cartoons (ep. pilota) ReteCartoon Network 1ª TV24 agosto 2001 – 9 novembre 2007 Stagioni6 Episodi84 (completa) Durata ep.6 min (ep. pilota)...

American baseball player Baseball player Rob DibbleDibble pitching for the Cincinnati Reds in 1991PitcherBorn: (1964-01-24) January 24, 1964 (age 60)Bridgeport, Connecticut, U.S.Batted: LeftThrew: RightMLB debutJune 29, 1988, for the Cincinnati RedsLast MLB appearanceSeptember 30, 1995, for the Milwaukee BrewersMLB statisticsWin–loss record27–25Earned run average2.98Strikeouts645Saves89 Teams Cincinnati Reds (1988–1993) Chicago White Sox (1995) Milwauk...

2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会奥地利代表團奥地利国旗IOC編碼AUTNOC奧地利奧林匹克委員會網站www.olympia.at(德文)2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会(東京)2021年7月23日至8月8日(受2019冠状病毒病疫情影响推迟,但仍保留原定名称)運動員75參賽項目21个大项旗手开幕式:托马斯·扎亚克(英语:Thomas Zajac)和塔尼娅·弗兰克(帆船)[1]闭幕式:安德烈亚斯·米勒(自行车)[2]...

本條目存在以下問題,請協助改善本條目或在討論頁針對議題發表看法。 此條目需要擴充。 (2013年1月1日)请協助改善这篇條目,更進一步的信息可能會在討論頁或扩充请求中找到。请在擴充條目後將此模板移除。 此條目需要补充更多来源。 (2013年1月1日)请协助補充多方面可靠来源以改善这篇条目,无法查证的内容可能會因為异议提出而被移除。致使用者:请搜索一下条目的...

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (April 2020) BridesMarch 2009 cover of BridesEditorGabriella Rello Duffy(Editorial Director)Corinne Pierre-Louis(Senior Fashion Editor)Jessica Chassin(Senior Social Media Editor)FrequencyQuarterlyPublisherDotdash MeredithTotal circulation(2013)330,605[1]Founded1934CompanyIACCountryUSLanguageEnglishWebsitewww.brides.com Brides (stylized in all caps) is an American ...

Census Town in West Bengal, IndiaChhota SuzapurCensus TownChhota SuzapurLocation in West Bengal, IndiaShow map of West BengalChhota SuzapurChhota Suzapur (India)Show map of IndiaCoordinates: 24°54′59″N 88°05′37″E / 24.916376°N 88.093665°E / 24.916376; 88.093665Country IndiaStateWest BengalDistrictMaldaArea • Total0.9052 km2 (0.3495 sq mi)Population (2011) • Total11,216 • Density12,000/km2 (32,000...

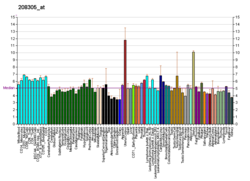

CYP19A1Struktur yang tersediaPDBPencarian Ortolog: PDBe RCSB Daftar kode id PDB3EQM, 3S79, 3S7S, 4GL5, 4GL7, 4KQ8PengidentifikasiAliasCYP19A1, ARO, ARO1, CPV1, CYAR, CYP19, CYPXIX, P-450AROM, cytochrome P450 family 19 subfamily A member 1ID eksternalOMIM: 107910 MGI: 88587 HomoloGene: 30955 GeneCards: CYP19A1 Lokasi gen (Tikus)Kr.Kromosom 9 (tikus)[1]Pita9 A5.3|9 29.49 cMAwal54,073,221 bp[1]Akhir54,175,394 bp[1]Pola ekspresi RNAReferensi data ekspresi selengk...

Vessel filled with a superheated transparent liquid Fermilab's disused 15-foot (4.57 m) bubble chamber The first tracks observed in John Wood's 1.5-inch (3.8 cm) liquid hydrogen bubble chamber, in 1954. A bubble chamber is a vessel filled with a superheated transparent liquid (most often liquid hydrogen) used to detect electrically charged particles moving through it. It was invented in 1952 by Donald A. Glaser,[1] for which he was awarded the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physics. ...

Racket sport Ping-pong redirects here. For other uses, see Ping-pong (disambiguation). Table tennisTable tennis at Liga ProHighest governing bodyITTFFirst played19th century, England[1][2]CharacteristicsContactNoTeam membersSingles or doublesTypeRacquet sport, indoorEquipmentPoly, 40 mm (1.57 in),2.7 g (0.095 oz)GlossaryGlossary of table tennisPresenceOlympicSince 1988ParalympicSince inaugural 1960 Summer Paralympics Table tennis (also known as ping-po...

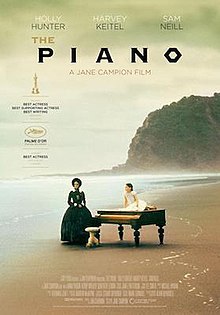

1993 film by Jane Campion This article is about the film. For the instrument, see Piano. For other uses, see Piano (disambiguation). The PianoTheatrical release posterDirected byJane CampionWritten byJane CampionProduced byJan ChapmanStarring Holly Hunter Harvey Keitel Sam Neill Anna Paquin Kerry Walker Genevieve Lemon CinematographyStuart DryburghEdited byVeronika JenetMusic byMichael NymanProductioncompaniesJan Chapman ProductionsCiBy 2000Distributed byBAC Films (France)Miramax[1] (...

Particle accelerator in Japan Superconducting Ring Cyclotron (SRC) The Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory is a multistage particle accelerator complex operated by Japan's Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science which is itself a part of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research. Located in Saitama, the RIBF generates unstable nuclei of all elements up to uranium and studies their properties. According to physicist Robert Janssens, [it] can produce the most intense beams of primary pa...

Municipality and town in Hidalgo, MexicoMolangoMunicipality and town SealMolangoLocation in MexicoCoordinates: 20°47′04″N 98°43′03″W / 20.78444°N 98.71750°W / 20.78444; -98.71750Country MexicoStateHidalgoMunicipal seatMolango de EscamillaArea • Total246.7 km2 (95.3 sq mi)Population (2005) • Total10,385 Molango (officially Molango de Escamilla ) is a town and one of the 84 municipalities of Hidalgo, in central...

此條目没有列出任何参考或来源。 (2013年10月12日)維基百科所有的內容都應該可供查證。请协助補充可靠来源以改善这篇条目。无法查证的內容可能會因為異議提出而被移除。 埃忒耳(Αἰθήρ / Aether,“上空”)在希腊神话中是“太空”的拟人化神,他代表了天堂。他是众神所呼吸的纯洁的天堂空气(一说是天堂的光线),不同于凡人所接触的空气(ἀήρ / air)。在赫西�...

South African newspaper City PressTypeSouth African news brandOwner(s)Media24EditorMondli MakhanyaFounded1982 (as Golden City Press)1983 (renamed City Press)LanguageEnglishHeadquartersJohannesburg, Gauteng, South AfricaSister newspapersRapportOCLC number70724022 Websitewww.news24.com/citypress City Press is a South African news brand that publishes on multiple platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed nationally on Sunday, and it has a daily newsletter, online platform, and other s...

Kerstin Bernhard Kerstin Bernhard och Lennart af Petersens 1951.Född27 augusti 1914[1][2][3]Lidingö församling[2], SverigeDöd30 september 2004[1] (90 år)Lidingö församling, SverigeBegravdLidingö församlings kyrkogård[4]Medborgare iSverigeSysselsättningFotografFöräldrarEdvard Bernhard[2]SläktingarCarl Gustaf Bernhard (syskon)Redigera Wikidata Kerstin Boel Bernhard, född 27 augusti 1914 på Lidingö, död 30 september 2004 på Lidingö, var en svensk fotograf. Biog...

Japanese artist (1895–1997) Sukiya Bridge, woodblock print by Un'ichi Hiratsuka by 1945 Un'ichi Hiratsuka (平塚 運一, Hiratsuka Un'ichi, November 17, 1895 – November 18, 1997), born in Matsue, Shimane, was a Japanese woodblock printmaker. He was one of the prominent leaders of the sōsaku hanga (creative print) movement in 20th century Japan. Hiratsuka's father was a shrine carpenter, and his grandfather was an architect who designed houses and temples. Therefore, the artist was i...