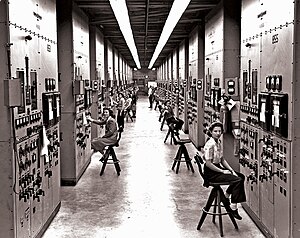

Calutron Girls

|

Read other articles:

Arena MonterreyLa ArenaBerkas:Arena-Monterrey-Logo.pngLokasiAve. Madero #2500 Oriente, Colonia Obrera Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico C.P. 64800Koordinat25°40′51.03″N 100°17′17.64″W / 25.6808417°N 100.2882333°W / 25.6808417; -100.2882333Koordinat: 25°40′51.03″N 100°17′17.64″W / 25.6808417°N 100.2882333°W / 25.6808417; -100.2882333PemilikPublimax México dan TV AztecaOperatorZignia LiveKapasitas17,599KonstruksiMulai pembang...

Kaisar Taizu dari JinKaisar Dinasti JinBerkuasa28 Januari 1115 – 19 September 1123PenerusKaisar Taizong dari JinInformasi pribadiKelahiran1 Agustus 1068Kematian19 September 1123 (usia 55)Nama lengkapWanyan Min (nama sinifikasi)Aguda (nama Jurchen)Shouguo (收國; 1115–1116)Tianfu (天輔; 1117–1123)Nama anumertaKaisar Yingqian Yuyun Zhaode Dinggong Renming Zhuangxiao Dasheng Wuyuan (應乾興運昭德定功仁明莊孝大聖武元皇帝)Nama kuilTaizu (太祖)AyahHeliboIbuLady NalanPasa...

1981 studio album by Chaz JankelChasanovaStudio album by Chaz JankelReleased1981RecordedJanuary–July 1981StudioEastcote Products Recording Studios (London)Genre Electronic funk blue-eyed soul reggae Length37:34LabelA&MProducer Philip Bagenal Chaz Jankel Peter Van Hooke Chaz Jankel chronology Chas Jankel(1980) Chasanova(1981) Chazablanca(1983) Singles from Chasanova 109Released: 1981 QuestionnaireReleased: 1981 Glad to Know YouReleased: 1981 Chasanova is the second solo studio a...

Stasiun Shin Kanō新加納駅Stasiun Shin Kanō, Juli 2017Lokasi1 Chome Nakahamamichō, Kakamigahara-shi, Gifu-ken 504-0034JepangKoordinat35°23′57″N 136°49′27″E / 35.3993°N 136.8243°E / 35.3993; 136.8243Koordinat: 35°23′57″N 136°49′27″E / 35.3993°N 136.8243°E / 35.3993; 136.8243Operator MeitetsuJalur■Jalur Meitetsu KakamigaharaLetak6.6 km dari Meitetsu-GifuJumlah peron2 peron sampingInformasi lainStatusTanpa stafKode ...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Bollnäs – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Place in Hälsingland, SwedenBollnäsBollnäs MissionskyrkaBollnäsShow map of Sweden GävleborgBollnäsShow map of SwedenCoordinates: 61°20...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Чайки (значения). Чайки Доминиканская чайкаЗападная чайкаКалифорнийская чайкаМорская чайка Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:Вторич...

ХристианствоБиблия Ветхий Завет Новый Завет Евангелие Десять заповедей Нагорная проповедь Апокрифы Бог, Троица Бог Отец Иисус Христос Святой Дух История христианства Апостолы Хронология христианства Раннее христианство Гностическое христианство Вселенские соборы Н...

فيكتور ليندلوف (بالسويدية: Victor Lindelöf) معلومات شخصية الاسم الكامل فيكتور نيلسون جورغين ليندلوف الميلاد 17 يوليو 1994 (العمر 29 سنة)فيستيروس، السويد الطول 1.87 م (6 قدم 2 بوصة) مركز اللعب قلب الدفاع الجنسية السويد الوزن +82 كيلوغرام معلومات النادي النادي الحالي ما�...

منتخب أوكرانيا لكرة القدم (بالأوكرانية: Збірна України з футболу) معلومات عامة بلد الرياضة أوكرانيا الفئة كرة القدم للرجال رمز الفيفا UKR تاريخ التأسيس 1991 الاتحاد اتحاد أوكرانيا لكرة القدم كونفدرالية يويفا (أوروبا) الملعب الرئيسي ملعب أولمبيسكي الوطني ال...

County in Iowa, United States County in IowaFloyd CountyCountyCourthouse in Charles City with Veterans Memorial in frontLocation within the U.S. state of IowaIowa's location within the U.S.Coordinates: 43°03′24″N 92°47′02″W / 43.056666666667°N 92.783888888889°W / 43.056666666667; -92.783888888889Country United StatesState IowaFounded1851Named forCharles FloydSeatCharles CityLargest cityCharles CityArea • Total501 sq mi (1,300...

Disused conception of a person's racial or ethnic makeup Race History Historical concepts Biblical terminology for race Society Color terminology Race relations Racialization Racism (scientific racism) Racial equality Racial politics Sociology of race Race and... Crime (United Kingdom, United States) Genetics Health (United States) Horror films Intelligence (history) Neuroscience Sexuality Society Sports Video games By location Race and ethnicity in censuses Brazil Colombia Latin America Unit...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع بلدة لينكولن (توضيح). بلدة لينكولن الإحداثيات 43°56′58″N 85°30′37″W / 43.949444444444°N 85.510277777778°W / 43.949444444444; -85.510277777778 [1] تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة أوسيولا خصائص جغرافية المساحة 35.5 ميل مربع ار�...

XBQ-3 Role Flying bombType of aircraft National origin United States Manufacturer Fairchild Aircraft First flight July 1944 Primary user United States Army Air Forces Number built 2 Developed from AT-21 Gunner The Fairchild BQ-3, also known as the Model 79, was an early expendable unmanned aerial vehicle – referred to at the time as an assault drone – developed by Fairchild Aircraft from the company's AT-21 Gunner advanced trainer during the Second World War for use by the United St...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Univers (homonymie). Ne doit pas être confondu avec L'Univers illustré. L'Univers Première de l'Univers après sa suspension en 1860. Pays France Langue Français Périodicité Quotidien Genre Presse d'opinion Date de fondation 1833 Date du dernier numéro 1919 Ville d’édition Paris modifier L'Univers est un journal quotidien catholique français, fondé en 1833 par l'abbé Jacques-Paul Migne et disparu en 1919. Racheté par le comte de Montalemb...

此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充。 (2023年7月8日)若您熟悉来源语言和主题,请协助参考外语维基百科扩充条目。请勿直接提交机械翻译,也不要翻译不可靠、低品质内容。依版权协议,译文需在编辑摘要注明来源,或于讨论页顶部标记{{Translated page}}标签。 弗农·路易斯·帕灵顿出生1871年8月3日 奥罗拉 逝世1929年6月16日、1921年6月16日 (57歲)母校哈佛大...

Patinação artística nos Jogos Olímpicos de Inverno de 2010 Individual masc fem Duplas misto Dança no gelo misto Apresentação de gala Pódio da competição em Vancouver As competições de duplas da patinação artística nos Jogos Olímpicos de Inverno de 2010 foram disputadas no Pacific Coliseum em Vancouver, Colúmbia Britânica em 14 e 15 de fevereiro de 2010, sendo a final disputada às 17:00 (UTC-8). [1] Medalhistas Ouro CHN Shen Xue e Zhao Hongbo Prata CHN Pang Qing e Tong Jian...

Motor race Indy Grand Prix of LouisianaIndyCar SeriesVenueNOLA Motorsports ParkLocationAvondale, Louisiana29°53′1″N 90°11′52″W / 29.88361°N 90.19778°W / 29.88361; -90.19778First race2015Last race2015Distance205.5 miles (330.7 km)Laps75Circuit informationSurfaceAsphaltLength2.74 mi (4.41 km)Turns13 The Indy Grand Prix of Louisiana was an IndyCar Series race held at NOLA Motorsports Park in Avondale, Louisiana in 2015.[1][2] The...

Town on the Isle of Lewis, in Scotland This article is about the Scottish town. For other uses, see Stornoway (disambiguation). Human settlement in ScotlandStornowayScottish Gaelic: SteòrnabhaghScots: StornowaStornowayLocation within the Outer HebridesArea3.16 km2 (1.22 sq mi)Population4,800 (2022)[1]• Density1,519/km2 (3,930/sq mi)DemonymSteòrnabhach, StornowegianLanguageEnglishScottish GaelicOS grid referenceNB426340• Edinburgh197&#...

Ability of a body to store an electrical charge For capacitance of blood vessels, see Compliance (physiology). Common symbolsCSI unitfaradOther unitsμF, nF, pFIn SI base unitsF = A2 s4 kg−1 m−2Derivations fromother quantitiesC = charge / voltageDimension L − 2 M − 1 T 4 I 2 {\displaystyle {\mathsf {L}}^{-2}{\mathsf {M}}^{-1}{\mathsf {T}}^{4}{\mathsf {I}}^{2}} Articles aboutElectromagnetism Electricity Magnetism Optics History Computational Textbooks Phenomena Elec...

Basque civil decoration AwardCross of the Tree of GernikaTypeCivil medalLocationBasque CountryCountrySpainPresented byLehendakariEstablished2 May 1983[1]Total9Ribbon bars for Basques and non-Basques PrecedenceNext (lower)Lan Onari The Cross of the Tree of Gernika (Basque: Gernikako Arbolaren Gurutzea, Spanish: Cruz del Árbol de Gernika) is a civil medal awarded in the Basque Country, Spain. It is awarded by the Basque Government to people who have distinguished themselves in the...