Bolitoglossa

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Letak Oblast Zakarpattia di Ukraina. Lambang Rusyns. Rutenia Karpatia, Karpato-Ukraina, atau Zakarpattia (bahasa Rusyn dan bahasa Ukraina: Карпатська Русь, Karpats’ka Rus’; atau Закарпаття, Zakarpattya; bahasa Slowakia dan bahasa Ceko: Podkarpatská Rus;[1] bahasa Hungaria: Kárpátalja; bahasa Rumania: Transcarpatia; bahasa Polandia: Zakarpacie; Jerman: Karpatenukrainecode: de is deprecated ) adalah sebuah wilayah yang terletak di Eropa...

Часть серии статей о Холокосте Идеология и политика Расовая гигиена · Расовый антисемитизм · Нацистская расовая политика · Нюрнбергские расовые законы Шоа Лагеря смерти Белжец · Дахау · Майданек · Малый Тростенец · Маутхаузен ·&...

Artikel atau bagian mungkin perlu ditulis ulang agar sesuai dengan standar kualitas Wikipedia. Anda dapat membantu memperbaikinya. Halaman pembicaraan dari artikel ini mungkin berisi beberapa saran. Biografi ini memerlukan lebih banyak catatan kaki untuk pemastian. Bantulah untuk menambahkan referensi atau sumber tepercaya. Materi kontroversial atau trivial yang sumbernya tidak memadai atau tidak bisa dipercaya harus segera dihapus, khususnya jika berpotensi memfitnah.Cari sumber: Jalalu...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant le droit français. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Article 88-5 de la Constitution du 4 octobre 1958 Données clés Présentation Pays France Langue(s) officielle(s) Français Type Article de la Constitution Adoption et entrée en vigueur Législature XIIe législature de la Cinquième République française Gouvernement Jean-Pierre Raffarin (3e) Promulgat...

Political party in Poland RACJA Polskiej Lewicy LeaderJan CedzyńskiFounded8 August 2002Dissolved23 November 2013Merged intoYour MovementHeadquartersul. Emilii Plater 55/81, 00-113 WarsawIdeologySocial democracyAnti-clericalismPolitical positionCentre-leftWebsitewww.racja.euPolitics of PolandPolitical partiesElections Reason of the Polish Left, or Reason Party (Polish: RACJA Polskiej Lewicy; RACJA; RACJA PL), was an anti-clerical[1] minor political party in Poland. It wa...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Space Research Centre of Polish Academy of Sciences – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Space Research CentreCentrum Badań KosmicznychAgency overviewAbbreviationSRCFormed29 September 1976TypeSpace agencyHead...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento generi cinematografici non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Boris Karloff in Frankenstein (1931)Il cinema dell'orrore o cinema horror è un genere cinematografico caratterizzato quasi sempre da personaggi immaginari e mostruosi, situazioni macabre, irraziona...

Навчально-науковий інститут інноваційних освітніх технологій Західноукраїнського національного університету Герб навчально-наукового інституту інноваційних освітніх технологій ЗУНУ Скорочена назва ННІІОТ ЗУНУ Основні дані Засновано 2013 Заклад Західноукраїнський �...

United States Navy admiral For other people with the same name, see Daniel Murphy. Daniel MurphyPictured as a rear admiral in 1973BornMarch 24, 1922Brooklyn, New York City, U.S.DiedSeptember 21, 2001(2001-09-21) (aged 79)Rockville, Maryland, U.S.Place of burialArlington National CemeteryAllegianceUnited States of AmericaService/branch United States NavyYears of service1943–1977Rank AdmiralCommands heldSixth FleetUSS BenningtonBattles/warsWorld War IIVietnam WarAwardsDefense D...

British TV series or programme Hotel TrubbleTitle card used from Series 2 onwards, showing (l-r) Tanya Franks (Dolly), Dominique Moore (Sally), Sam Phillips (Jamie), Sheila Bernette (Mrs. Poshington) and Gary Damer (Lenny).GenreComedy dramaDeveloped byBBCFilm and General Productions LtdDirected byNatalie BaileyStarringDominique Moore Sam Phillips Gary Damer Sheila Bernette Tanya Franks (Series 2–3)Susan Wokoma (Series 3)Country of originUnited KingdomOriginal languageEnglishNo. of series3N...

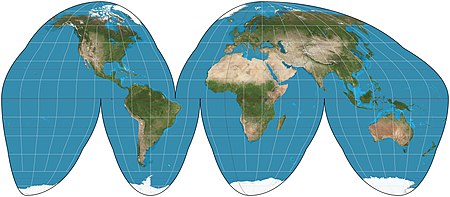

Проекция Гуда для Земного шара Проекция Гуда (гомолосинусоидальная проекция Гуда) — псевдоцилиндрическая равновеликая композитная картографическая проекция используемая в картах мира. Для уменьшения искажений обычно изображается с разрывами. Проекция была разраб...

2018 mass shooting in Parkland, Florida, US Parkland high school shootingNikolas Cruz on the second floorParklandParkland (Florida)Show map of FloridaParklandParkland (the United States)Show map of the United StatesLocationParkland, Florida, U.S.Coordinates 26°18′19″N 80°16′06″W / 26.3053°N 80.2683°W / 26.3053; -80.2683 (Shooting) (shooting) 26°17′23″N 80°17′14″W / 26.2897°N 80.2871°W / 26.2897; -80.2871 (...

Province of Canada Newfoundland redirects here. For the island, see Newfoundland (island). For other uses, see Newfoundland (disambiguation). Province in CanadaNewfoundland and Labrador Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador (French)[1]Province FlagCoat of armsMotto(s): Quaerite prime regnum Dei (Latin)Seek ye first the kingdom of God (Matthew 6:33) BC AB SK MB ON QC NB PE NS NL YT NT NU Coordinates: 53°13′48″N 59°59′57″W / 53.23000°N 59.99917°W / 53.230...

Entry for India in ISO 3166-2 States and union territories of India ordered by Area Population GDP (per capita) Abbreviations Access to safe drinking water Availability of toilets Capitals Child nutrition Crime rate Ease of doing business Electricity penetration Exports Fertility rate Forest cover Highest point HDI Home ownership Household size Human trafficking Infant mortality rate Institutional delivery Life expectancy at birth Literacy rate Media exposure Number of vehicles Number of vote...

Roman hoard Capheaton TreasureThe Capheaton Treasure, as displayed in the British MuseumMaterialSilverCreated2nd-3rd Century ADPresent locationBritish Museum, LondonRegistrationP&EE 1824.4-89.59-65 The Capheaton Treasure is an important Roman silver hoard found in the village of Capheaton in Northumberland, north-east England. Since 1824, it has been part of the British Museum's collection.[1] Discovery The hoard was discovered in 1747 in the village of Capheaton near Kirkwhelping...

DunevideogiocoVersione MS-DOSPiattaformaAmiga, Sega Mega CD, MS-DOS Data di pubblicazione1992 GenereAvventura, strategia TemaDune OrigineFrancia SviluppoCryo Interactive PubblicazioneVirgin Interactive DesignRémi Herbulot Modalità di giocoGiocatore singolo Periferiche di inputMouse, tastiera, joystick SupportoFloppy (2), CD-ROM SerieDune Seguito daDune II Dune è un videogioco, primo della serie e ispirato all'omonimo ciclo di romanzi di fantascienza di Frank Herbert. Venne svil...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Concile de Toulouse (1229). Plusieurs conciles se sont tenus à Toulouse. Historique Basilique Saint-Sernin de Toulouse 355 : Concile des Gaules (ou à Poitiers). 506 ou 507 : Convoqué par Alaric II pour faire adopter son code de loi. Il n'est connu que par une lettre de Césaire d'Arles. 828 et 829 : Sous la présidence de l'archevêque d'Arles, Nothon[1] ; les actes de ces conciles sont perdus. Juin 844 : Charles II le Chauve prom...

Particolare dello zoccolo del minareto della moschea Bibi Khanum a Samarcanda, in Uzbekistan. I pannelli verticali ad arco sono decorati con diversi modelli geometrici e con stelle a 10, 8 e 5 punte. Una porta della Madrasa di Ben Youssef a Marrakech. Le porte in legno sono scolpite con un modello di girih con stelle a 16 punte. L'arco è circondato da arabeschi; su entrambi i lati vi è una banda di calligrafia islamica, colorata con piastrelle zellige geometriche con stelle a 8 punte. I mot...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Ceko (disambiguasi). Republik CekoČeská republika (Ceko) Bendera Lambang Semboyan: Pravda vítězí (Kebenaran menang)Lagu kebangsaan: Kde domov můj (Di Mana Rumahku Berada) Perlihatkan BumiPerlihatkan peta EropaPerlihatkan peta BenderaLokasi Ceko (hijau gelap)– di Eropa (hijau & abu-abu)– di Uni Eropa (hijau)Ibu kota(dan kota terbesar)Praha50°5′N 14°28′E / 50.083°N 14...

سرغي سوبيانين (بالروسية: Сергей Семёнович Собянин) عمدة موسكو الثالث تولى المنصب21 أكتوبر 2010 الرئيس دميتري مدفيديف،فلاديمير بوتين يوري لوجكوف محافظ تيومين أوبلاست في المنصب26 يناير 2001 – 14 نوفمبر 2005 معلومات شخصية الميلاد 21 يونيو 1958 مواطنة روسيا (1991–) الديانة ال�...