Battle of Guinegate (1479)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

10050 Cielo DriveJalan menuju vila tahun 1997Informasi umumJenisRumahGaya arsitekturFrench CountryLokasiBenedict Canyon, Los AngelesKoordinat34°05′38″N 118°25′57″W / 34.093895°N 118.432467°W / 34.093895; -118.432467Koordinat: 34°05′38″N 118°25′57″W / 34.093895°N 118.432467°W / 34.093895; -118.432467Mulai dibangun1942Rampung1944Dibongkar1994Data teknisLuas lantai4.600 sq ft (430 m2)Desain dan konstruksiArsit...

Artikel ini perlu dikembangkan agar dapat memenuhi kriteria sebagai entri Wikipedia.Bantulah untuk mengembangkan artikel ini. Jika tidak dikembangkan, artikel ini akan dihapus. Letak Cotitx di Mallorca Costitx merupakan nama kota di Spanyol. Letaknya di bagian timur. Tepatnya di Wilayah Otonomi Kepulauan Balearik, Spanyol. Pada tahun 2005, kota ini memiliki jumlah penduduk sebanyak 1.004 jiwa dan memiliki luas wilayah 15,35 km². lbsKotamadya di Kepulauan BalearsMallorca Alaró Alcúdia ...

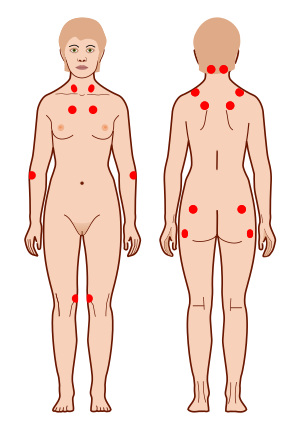

FibromyalgiaLokasi dari sembilan titik nyeri berpasangan berdasarkan kriteria American College of Rheumatology tahun 1990 untuk fibromyalgiaInformasi umumNama lainSindrom FibromyalgiaPelafalan/ˌfaɪbroʊmaɪˈældʒə/[1]SpesialisasiPsikiatri, reumatologi, neurologi[2]PenyebabBelum diketahui[3][4]Aspek klinisGejala dan tandaNyeri yang meluas, rasa lelah, gangguan tidur[5][3]Awal munculUsia pertengahan[4]DurasiJangka lama[5]Diagn...

Jack and JillPoster rilis teatrikalSutradaraDennis DuganProduserAdam SandlerJack GiarraputoTodd GarnerSkenarioAdam SandlerSteve KorenCeritaBen ZookPemeranAdam SandlerAl PacinoKatie HolmesPenata musikRupert Gregson-WilliamsWaddy WachtelSinematograferDean CundeyPenyuntingTom CostainPerusahaanproduksiHappy Madison ProductionsDistributorColumbia PicturesTanggal rilis 11 November 2011 (2011-11-11) Durasi91 menit[1]NegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaInggrisAnggaran$79 juta[2]Pend...

Strada statale 480di UruriLocalizzazioneStato Italia Regioni Molise Puglia Province Campobasso Foggia DatiClassificazioneStrada statale InizioSS 87 presso Larino Fineex SS 376 presso Serracapriola Lunghezza31,825[1][2] km Provvedimento di istituzioneD.M. 6/03/1965 - G.U. 96 del 16/04/1965[3] GestoreTratte ANAS: nessuna (dal 2001 la gestione è passata alla Provincia di Campobasso e alla Provincia di Foggia) Percorso Manuale La ex strada statale...

Tanah aluvial di daerah Amazon Basin, Brasil Aluvial adalah jenis tanah yang terbentuk karena endapan.[1] Daerah endapan terjadi di sungai, danau yang berada di dataran rendah, ataupun cekungan yang memungkin kan terjadinya endapan.[1] Tanah aluvial memiliki manfaat di bidang pertanian salah satunya untuk mempermudah proses irigasi pada lahan pertanian. [2] Tanah ini terbentuk akibat endapan dari berbagai bahan seperti aluvial dan koluvial yang juga berasal dari berbag...

Об экономическом термине см. Первородный грех (экономика). ХристианствоБиблия Ветхий Завет Новый Завет Евангелие Десять заповедей Нагорная проповедь Апокрифы Бог, Троица Бог Отец Иисус Христос Святой Дух История христианства Апостолы Хронология христианства Ран�...

2016 single by BeyoncéFormationSingle by Beyoncéfrom the album Lemonade ReleasedFebruary 6, 2016 (2016-02-06)Recorded2015StudioQuad Recording Studios, New York CityGenreR&BtrapbounceLength3:26LabelParkwoodColumbiaSongwriter(s)Beyoncé KnowlesKhalif BrownAsheton HoganMichael Len Williams IIProducer(s)BeyoncéMike Will Made ItBeyoncé singles chronology Hymn for the Weekend (2016) Formation (2016) Sorry (2016) Music videoFormation on YouTube Formation is a song recorded by...

Untuk kegunaan lainnya, lihat CP (disambiguasi). Artikel ini adalah tentang kereta api di Canada. Untuk Kode Stasiun CP di Cilacap, lihat Stasiun Cilacap Canadian Pacific Railway, LimitedPeta jaringan Canadian Pacific (tidak termasuk jalur DM&E, CMQ, atau KCS)IkhtisarKantor pusatCalgary, Alberta, KanadaMarkah laporanCPLokalKanada dengan cabang keAmerika Serikat, mencakup Chicago,Detroit, Minneapolis danNew York CityTanggal beroperasi16 Februari 1881–14 April 2023Lain-lainSitus webww...

Disambiguazione – Jaspers rimanda qui. Se stai cercando il gruppo musicale italiano, vedi Jaspers (gruppo musicale). Karl Jaspers (1913) Karl Theodor Jaspers (Oldenburg, 23 febbraio 1883 – Basilea, 26 febbraio 1969) è stato un filosofo e psichiatra tedesco con cittadinanza svizzera[1]. Ha dato un notevole impulso alle riflessioni nei campi della psichiatria, della psicologia, della filosofia, della teologia e della politica. Indice 1 Biografia 2 Contributi alla psichiatr...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Горностай (значения). Горностай Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:Челюстнороты...

For the police officer in India, see Edward Arthur Dodwell. Edward Dodwell1828 drawing of DodwellBorn(1767-11-30)30 November 1767Dublin, IrelandDied13 May 1832(1832-05-13) (aged 65)Rome, Papal StatesOccupationWriter, painterGenretravel literatureNotable worksViews in GreeceSpouseGiraud Edward Dodwell (30 November 1767 – 13 May 1832) was an Irish painter, traveller and a writer on archaeology. Painting of the bazaar at Athens, by Dodwell. West Front of the Parthenon, Views ...

قرية الشيسع - قرية - تقسيم إداري البلد اليمن المحافظة محافظة حضرموت المديرية مديرية رماة العزلة عزلة رماة السكان التعداد السكاني 2004 السكان 50 • الذكور 27 • الإناث 23 • عدد الأسر 5 • عدد المساكن 5 معلومات أخرى التوقيت توقيت اليمن (+3 غرينيتش) تعديل ...

Fenomena optis adalah segala aktivitas yang dilihat dari hasil interaksi cahaya dan materi. Lihat juga daftar topik optik dan optik. Fatamorgana adalah contoh dari fenomena optis. Fenomena umum optik sering disebabkan oleh interaksi dari cahaya Matahari atau bulan dengan atmosfer, awan, air, atau debu dan material lainnya. Satu contoh umum yaitu pelangi, ketika cahaya Matahari dipantulkan dan dibiaskan oleh tetesan-tetesan air. Beberapa, seperti sinar hijau, sangat jarang terjadi sehingga kad...

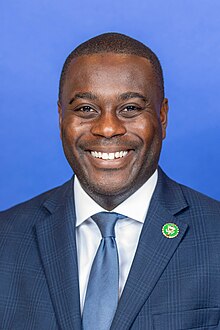

American politician (born 1987) Gabe AmoAmo in 2023Member of the U.S. House of Representativesfrom Rhode Island's 1st districtIncumbentAssumed office November 13, 2023Preceded byDavid Cicilline Personal detailsBornGabriel Felix Kofi Amo (1987-12-11) December 11, 1987 (age 36)Pawtucket, Rhode Island, U.S.Political partyDemocraticEducationWheaton College (BA)Merton College, Oxford (MSc)WebsiteHouse website Gabriel Felix Kofi Amo (born December 11, 1987)[1] is an Ame...

マレーシアの政治家マハティール・ビン・モハマドMahathir bin Mohamad マハティール・ビン・モハマド(2018年8月3日)生年月日 (1925-07-10) 1925年7月10日(99歳)[注釈 1]出生地 イギリス領マラヤ、クダ州アロースター所属政党 (バリサン・ナショナル→)(統一マレー国民組織→)祖国闘士党(英語版)称号 桐花大綬章配偶者 シティ・ハスマ子女 7 (ムクリズ、マリナ�...

In signal processing, a causal filter is a linear and time-invariant causal system. The word causal indicates that the filter output depends only on past and present inputs. A filter whose output also depends on future inputs is non-causal, whereas a filter whose output depends only on future inputs is anti-causal. Systems (including filters) that are realizable (i.e. that operate in real time) must be causal because such systems cannot act on a future input. In effect that means the output s...

إن حيادية وصحة هذه المقالة محلُّ خلافٍ. ناقش هذه المسألة في صفحة نقاش المقالة، ولا تُزِل هذا القالب من غير توافقٍ على ذلك. (نقاش) العلاقات السعودية العراقية العراق السعودية السفارات سفارة المملكة العربية الـسعودية في بغداد السفير عبد العزيز بن خالد الشم...

City in Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine Zimogorye redirects here. For other places with the same name, see Zimogorye (rural locality). City in Luhansk Oblast, UkraineZymohiria Зимогір'яCity Coat of armsZymohiriaLocation of Zymohiria within UkraineShow map of UkraineZymohiriaZymohiria (Luhansk Oblast)Show map of Luhansk OblastCoordinates: 48°34′55″N 38°55′55″E / 48.58194°N 38.93194°E / 48.58194; 38.93194Country UkraineOblastLuhansk OblastRaionAlchevsk R...

1755 battle of the French and Indian War Battle of Fort BeauséjourPart of the French and Indian WarRobert Monckton by Benjamin WestDateJune 3–16, 1755LocationNear present-day Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada45°51′56″N 64°17′27″W / 45.86556°N 64.29083°W / 45.86556; -64.29083Result British victoryBelligerents FranceMi'kmaq militiaAcadian militia Great BritainCommanders and leaders Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor Robert MoncktonGeorge ScottNav...