Ain't We Got Fun

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Katedral Katolik Suriah BayonneKatedral Santo YosefSt. Joseph CathedralKatedral Katolik Suriah Bayonne40°39′49.9″N 74°07′02.4″W / 40.663861°N 74.117333°W / 40.663861; -74.117333Koordinat: 40°39′49.9″N 74°07′02.4″W / 40.663861°N 74.117333°W / 40.663861; -74.117333Lokasi21 E. 23rd St.Bayonne, New JerseyNegaraAmerika SerikatDenominasiGereja Katolik Roma(sui iuris: Gereja Katolik Suriah)SejarahDidirikan2011ArsitekturStatusKat...

Bandar Udara LoikawIATA: LIWICAO: VYLKInformasiLokasiLoikaw, BurmaKetinggian dpl896 mdplLandasan pacu Arah Panjang Permukaan kaki m 01/19 5.200 1.585 Bitumen Bandar Udara Loikaw (IATA: LIW, ICAO: VYLK) adalah bandar udara di Loikaw, Myanmar. Bandar udara ini memiliki satu landasan pacu. Landasan pacu di bandar udara ini memiliki panjang 5.200 kaki atau 1.585 meter. Maskapai penerbangan dan tujuan Myanma Airways (Yangon) Referensi Informasi bandar udara World Aero Data untuk VYL...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (août 2022). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références » En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ? Comm...

Two-color broken check pattern For the plant used commonly known as Houndstooth, see Cynoglossum officinale. Houndstooth pattern Houndstooth, hounds tooth check or hound's tooth (and similar spellings), also known as dogstooth, dogtooth, dog's tooth, (French: pied-de-poule, lit. 'hen's foot'), is a duotone textile pattern characterized by a tessellation of light and dark solid checks alternating with light-and-dark diagonally-striped checks—similar in pattern to gingham pl...

نفرو الثالثة معلومات شخصية تاريخ الميلاد القرن 20 ق.م تاريخ الوفاة القرن 20 ق.م الزوج سنوسرت الأول الأولاد أمنمحات الثاني الأب أمنمحات الأول عائلة الأسرة المصرية الثانية عشر الحياة العملية المهنة سياسية تعديل مصدري - تعديل نفرو الثالثة في الهير...

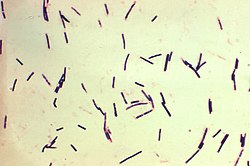

Cet article est une ébauche concernant la bactériologie. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Clostridium Un groupe de bactéries Clostridium tetaniClassification Domaine Bacteria Division Firmicutes Classe Clostridia Ordre Clostridiales Famille Clostridiaceae GenreClostridiumPrazmowski, 1880 Espèces de rang inférieur Clostridium acetobutylicum Clostridium aerotolerans Clostridium beijerinckii Clo...

Artikel ini membahas mengenai bangunan, struktur, infrastruktur, atau kawasan terencana yang sedang dibangun atau akan segera selesai. Informasi di halaman ini bisa berubah setiap saat (tidak jarang perubahan yang besar) seiring dengan penyelesaiannya. Fortune AraamesInformasi umumStatusDisetujuiLokasiDubai, Uni Emirat ArabPerkiraan rampung2008Data teknisJumlah lantai45Desain dan konstruksiArsitekDimensions Engineering ConsultantsPengembangNakheel Fortune Araames merupakan sebuah menara berti...

Ongoing COVID-19 viral pandemic in Eastern Visayas of the Philippines COVID-19 pandemic in Eastern VisayasDiseaseCOVID-19Virus strainSARS-CoV-2LocationEastern VisayasFirst outbreakWuhan, Hubei, ChinaIndex caseCatarmanArrival dateMarch 23, 2020(4 years, 1 week and 6 days)Confirmed cases67,099Recovered65,998Deaths867Government websitero8.doh.gov.ph The COVID-19 pandemic in Eastern Visayas is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by seve...

Australian Notes Act 1910Private currency issued by the City Bank of Sydney c. 1900Parliament of AustraliaAssented to16 September 1910Repealed14 December 1920Status: Repealed The Australian Notes Act 1910 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which allowed for the creation of Australia's first national banknotes. In conjunction with the Coinage Act 1909 it created the Australian pound as a separate national currency from the pound sterling. The act was enacted on 16 September 1910 b...

سارت علم شعار الاسم الرسمي (بالفرنسية: Sarthe) الإحداثيات 48°17′00″N 0°13′00″E / 48.283333333333°N 0.21666666666667°E / 48.283333333333; 0.21666666666667 [1] تاريخ التأسيس 4 مارس 1790 سبب التسمية نهر سارت تقسيم إداري البلد فرنسا[2][3] التقسيم الأعلى بايي دو �...

Tapanilan EräFounded1933 (sports club)1990 (floorball)1997 (Kendo)2008 (ZNKR Jōdō)CoachFloorball: Petteri Bergman (men)Kati Suomela (women)Kendo:Kari Jääskeläinen ZNKR Jōdō:Jarkko LakkistoLeagueSalibandyliiga (floorball) Tapanilan Erä is a Finnish sports club that was founded in 1933, with various teams in different disciplines. It is one of Finland's largest sporting clubs. Disciplines Martial Arts Boxing Judo Jujitsu Karate Kendo Ki-Aikido ZNKR Jōdō Other Archery Athletics Badmin...

Quinto è un nome proprio di persona italiano maschile[1][2]. Indice 1 Varianti 1.1 Varianti in altre lingue 2 Origine e diffusione 3 Onomastico 4 Persone 4.1 Antichi romani 5 Il nome nelle arti 6 Note 7 Bibliografia 8 Altri progetti Varianti Maschili: Quinzio[1][2] Alterati: Quintino[1] Femminili: Quinta[2], Quinzia Alterati: Quintilla[1] Varianti in altre lingue Basco: Kinto Bulgaro: Квинт (Kvint) Catalano: Quint[3] Latino...

Famili Jahe Periode Kampanium - Sekarang[1] PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N Zingiberaceae KecombrangTaksonomiDivisiTracheophytaSubdivisiSpermatophytesKladAngiospermaeKladmonocotsKladcommelinidsOrdoZingiberalesFamiliZingiberaceae Martinov, 1820 Tipe taksonomiZingiber Tata namaStatus nomenklaturnomen conservandum lbs Zingiberaceae, Suku temu-temuan, atau Suku jahe-jahean adalah salah satu suku anggota tumbuhan berbunga. Menurut sistem klasifikasi APG II suku ini termasuk ke dalam bangsa Z...

Set of physiological feedback interactions Schematic of the HPA axis (CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone) Hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal cortex The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis or HTPA axis) is a complex set of direct influences and feedback interactions among three components: the hypothalamus (a part of the brain located below the thalamus), the pituitary gland (a pea-shaped structure located below the hypothalamus), and ...

Zoo in Panama City Beach, FL Gulf World Marine ParkLogo of Gulf World Marine ParkDate openedMay 25th, 1970Location15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City Beach, FL 32413Annual visitors150,000Websitegulfworldmarinepark.com Gulf World Marine Park is a dolphinarium located in Panama City Beach, Florida. It has been open since 1970, and is one of only a few institutes in the United States to house rough-toothed dolphins. History Gulf World Marine Park was founded in 1969 by a group of five Alabama busi...

Indian drink SolkadhiSol kadhiTypeDrinkCourseAppetizerPlace of originIndiaRegion or stateKonkan region(coastal Maharashtra, Goa and parts of Karnataka)Main ingredientsKokum, Coconut milk Solkadhi is a type of drink, an appetizer originating from the Indian subcontinent, usually eaten with rice or sometimes drunk after or along with the meal. Popular in the Konkan regions, especially Goa, Mangalore and parts of coastal Maharashtra, it is made from coconut milk and dried kokum skins, whose anth...

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (January 2022) This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (December 2018) Two Mexican-American men, Francisco Arias and José Chamales, lynched in Santa Cruz, California, in 1877 The lynching of Frank McManus in Minneapolis, Minnesota for rape in 1882 This is a list of lynch...

NGC 6193 الكوكبة المجمرة[1] رمز الفهرس NGC 6193 (الفهرس العام الجديد)OCl 975 (Catalogue of Star Clusters and Associations)C 1637-486 (فهرس كالدويل) المكتشف جيمس دنلوب تاريخ الاكتشاف 1826 شاهد أيضًا: مجرة، قائمة المجرات تعديل مصدري - تعديل إن جي سي 6193 (NGC 6193) هو عنقود مفتوح ايحتوي على 27...

Martine Sagaert Martine Sagaert Données clés Naissance 28 octobre 1953 (70 ans) Asnières-sur-Seine (Seine) Activité principale professeur, essayiste, biographe, auteur de littérature jeunesse Auteur Langue d’écriture française modifier Martine Sagaert, née le 28 octobre 1953 à Asnières-sur-Seine (aujourd'hui dans les Hauts-de-Seine), est professeure, essayiste, biographe et auteure de littérature jeunesse. Biographie Martine Sagaert est professeure émérite de littérature...

2007 single by Beyoncé Get Me BodiedSingle by Beyoncéfrom the album B'Day ReleasedJuly 10, 2007RecordedApril 2006StudioSony Music Studios (New York City, New York)Genre Bounce R&B Length 3:25 (album version) 4:00 (radio edit) 6:18 (extended mix) Label Columbia Music World Songwriter(s) Beyoncé Knowles Kasseem Dean Sean Garrett Makeba Riddick Angela Beyincé Solange Knowles Producer(s) Beyoncé Knowles Swizz Beatz Sean Garrett Beyoncé singles chronology Beautiful Liar (2007) Get Me Bod...